At the Library, in the Lab, Saving History

From Appalachia to the American Southwest, local libraries are saving personal histories one public memory lab at a time.

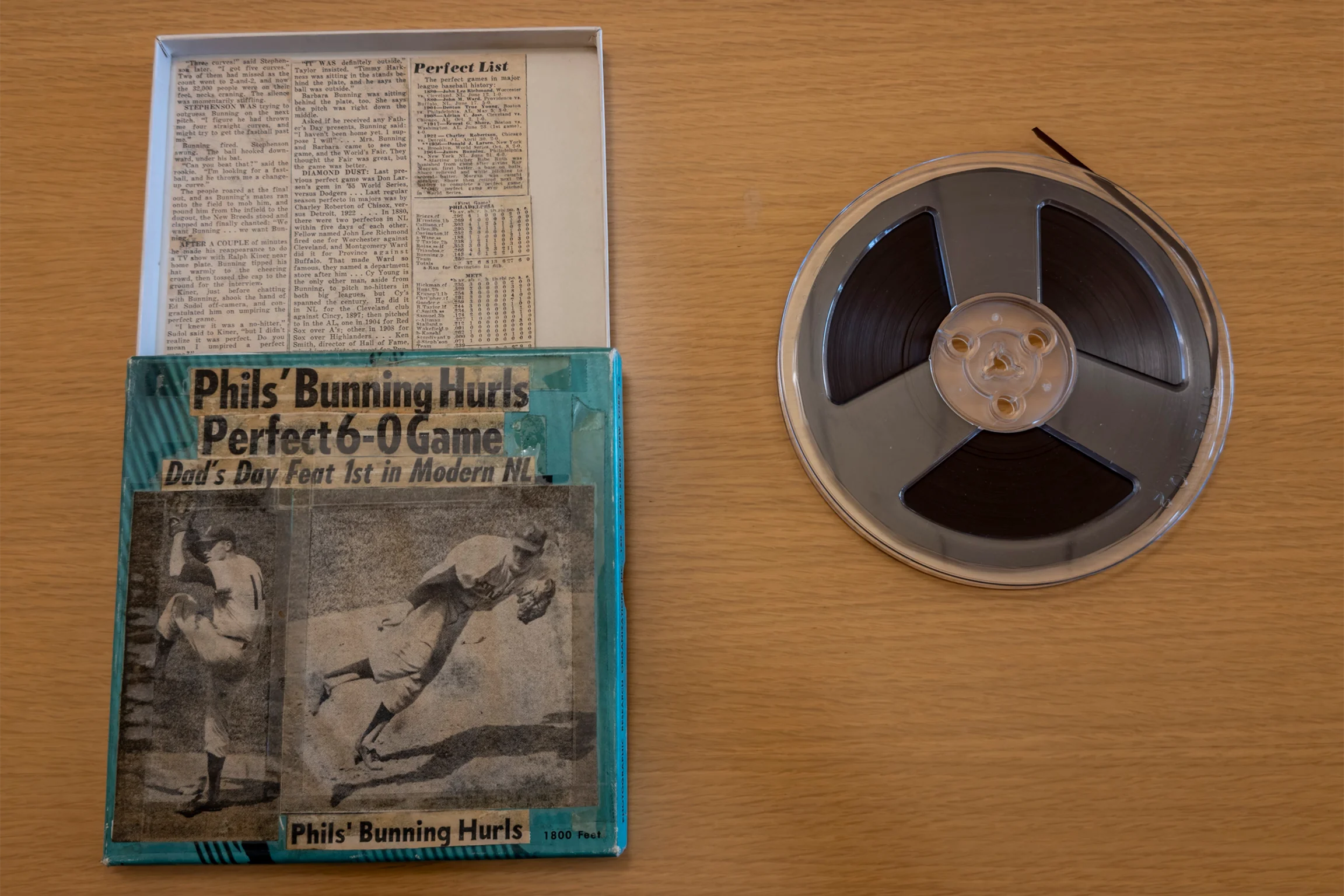

A highlight of Catherine Hoang’s job at the San Diego Public Library (SDPL) is watching her patrons’ excitement as they digitize their old photos, home movies, slides, and other analogue materials. It’s also seeing their sense of accomplishment as they master the technology to bring these memories back to life, be it their children’s first steps, summer holidays, or a wedding video.

“I really love seeing the look on their face when they're like, ‘Oh my gosh, that was me, Christmas of 1936, and that's my brother, and he's passed away.’ They want to share their whole life, and it just opens people up,” says Hoang, a public technology services librarian. There are “a lot of tears, a lot of fond memories, and it's just so touching to see.”

As part of her job, Hoang supports the library’s digital “memory labs,” one of many popping up in public library systems across the country to help people and communities preserve their histories. These personal archiving centers let patrons digitize their obsolete and analog media formats, and sometimes also create and share new content such as through recording oral histories. Mellon Foundation is supporting over 20 library systems in this work, with grant activities that include building and expanding memory lab locations, strengthening partnerships, and programming to connect underrepresented groups with memory lab resources.

SDPL is the largest cultural institution in the city, with low-to-moderate-income families making up almost 80 percent of its patrons. With Mellon support, SDPL will upgrade its two existing digital memory labs as well as create three new permanent labs and five pop-up mobile ones to circulate among the library’s branches. It hopes to benefit San Diegans more equitably with these expanded services in its 36 locations.

“The primary goal is to extend the reach to more communities to bridge the digital divide, and to give access to different communities of concern,” Hoang says. “Libraries are always that trusted place you go to seek information, and we are the collectors and preservers of most of the city's knowledge.”

They’re also looking to showcase the mix of people living in San Diego, which has a cultural heritage influenced by being a border city, its Native American communities, and the military. Through the I AM SAN DIEGO initiative, in 2024 the library will encourage patrons to tell their stories using video recording kiosks at SDPL’s branches.

“We have such a diverse and rich culture here in San Diego,” says Hoang. “We're a big melting pot.”

About 100 miles north of San Diego, the Los Angeles Public Library (LAPL) is also expanding its memory lab work to reach a wider swath of its service area. One of the biggest library systems in the country, LAPL has 73 locations that serve a hugely diverse population. It was also an early adopter of community collecting, digitization services, and personal archiving and memory labs, establishing a digitization program in 1997.

LAPL currently has one DIY, or do-it-yourself, memory lab at its Central Library downtown and a mobile memory lab. Mellon support will help the library system add six new memory labs and offer related programming and training. Patrons can use the labs, which will have cutting-edge technology such as 360-degree cameras, to capture their oral histories and scan objects, either for personal use or to share in LAPL’s special collections.

“The goal of the programming essentially is to democratize archiving to make it more accessible to people, to impart the knowledge and the technical skills, and to generally encourage people to preserve their materials,” says Aza Babayan, a LAPL community archives program manager.

LAPL is also planning to align its memory lab activities with its digital and special collections, including through a new advisory group that will help expand its archival collections on the Black and queer, Chicanx experiences as well as on the city’s unhoused community. “This is part of the process to expand special collections, to make them more inclusive,” says Babayan.

Reference Manager, Samuels Library

“We want to provide access for those people who might want to but don’t know how, don't have the resources, or don't know where else to go.”

Across the country in the Appalachian region, the Samuels Library has similar goals but on a smaller scale. Located in Front Royal, Virginia, the one-branch library system serves a rural community of more than 40,000 people. It’s the second subscription library or membership-supported library in the state, having been around since 1799.

In 2022, Samuels Library added a small digital memory lab. Now it’s using this grant to expand the lab’s services, enhance equipment, and hire a dedicated staff member. The library will also create a multi-purpose makerspace to house the memory lab and offer such things as sewing machines and sublimation printers.

“We want to provide access for those people who might want to but don't know how, don't have the resources, or don't know where else to go. We're able to bring that to the community through us,” says Rachael Roman, the library’s adult reference manager.

Samuels Library will also be digitizing its local history collections and hopes to connect with other organizations seeking to do the same. The region has a robust history, including related to the Civil War and its rural, working class, Appalachian, and Civil Rights heritage. The library also has a depository of documents on a local environmental disaster caused by the company Avtex Fibers. Ultimately, Library Director Erin Rooney says, they want to create an online database for local history collections.

“It is the history of our area, the history of the people who live here, and wanting to make sure we make that accessible for the future,” says Rooney. “Libraries can be repositories for local history, and once it's gone, it's gone.”

In Southeastern Colorado, the Pueblo City-County Library District (PCCLD) is also trying to preserve local history. The largest library district in the region, it serves nearly 170,000 people. In 2018, it built its first digital memory lab at the main branch. The lab has attracted mostly older patrons so far, says Aaron Ramirez, a PCCLD manager of local history and genealogy. Some have come in, for instance, to watch a VHS tape of a departed family member they hadn't seen in years, to be able to see and hear them again. Others have digitized old slides so they have a better way to show those images to their loved ones.

“The biggest benefit has been that people have access to the memories from their lives that were trapped on this obsolete media that they don't have the means to view or do anything with them,” Ramirez says. “The cost of scanning, using a vendor or services like that are fairly expensive. It's been about being able to connect people with the equipment and also the expertise of my staff to support them in that…By far, the comment I've gotten [most often] is that they're planning on sharing the results of their work with their friends and family. That's been the highest priority.”

PCCLD will continue to spread the wealth and add six permanent labs at partner locations, such as galleries, museums, and archives, and five mobile memory labs across 16 counties. It will also create a digital hub to store and display some of these materials provided by community members about their lives. One aim is to better highlight the region’s history, which includes it being a “frontier area,” under Spanish and Mexican rule, and the site of the Colorado Fuel and Iron Company headquarters. That history has left a legacy of diversity in the area, says Ramirez, including those with Hispanic, Latinx, and Chicanx ancestry. They also want to better capture those who currently live there.

“A lot of times for collections like ours—local history, genealogy collections, special collections—the public may think that it's disconnected or separate from their history, but with the memory lab work we encourage them and say, ‘Oh, this is important.’ Not only for their family, but also as a record of the culture and lives of people in the area,” he says. “The number one thing is to preserve the history and culture of the region and to inform people that their collections matter, that they're making history now, as we speak, in their everyday lives.”

Related