Rescuing the Nation’s Stories One Tape at a Time

A renewed effort to protect, preserve, and save America’s vast historical public media content depends, in large part, on a small group of unsung heroes.

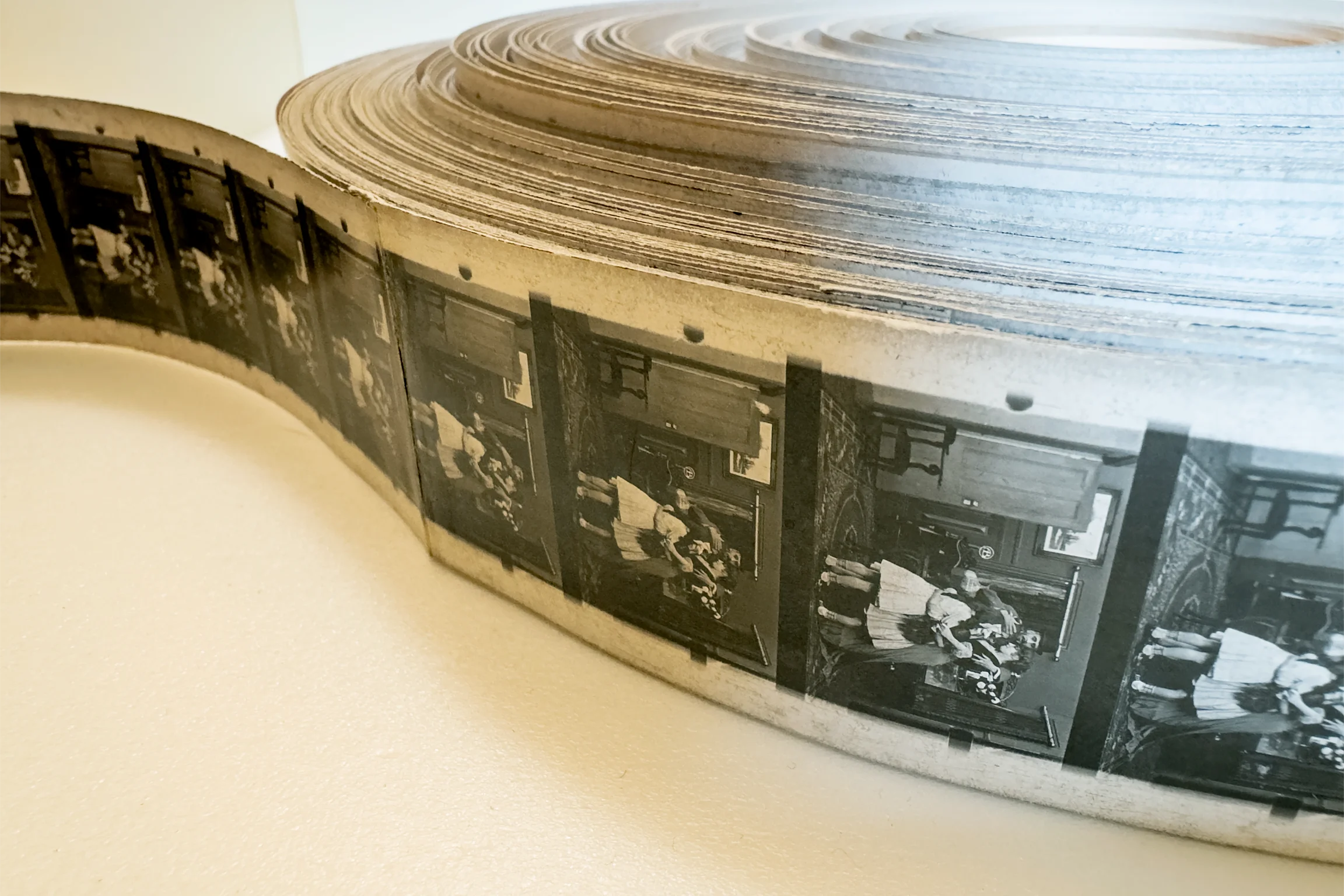

In the back rooms of public media organizations across the country, countless audio and video tapes collect the stories and voices that have shaped the American cultural landscape since the mid-twentieth century.

Though many don’t realize it, a treasure trove of radio and television programs documenting our complex national history—in ways groundbreaking for their time and surprisingly relevant today—are stored in unofficial archives, trapped on obsolete recording formats that very few people can access. Now, they’re at risk of degeneration and decay.

Thankfully, the Library of Congress has teamed up with the Boston-based public media producer GBH to improve their fate, and to make the riches accessible to everyone through the American Archive of Public Broadcasting (AAPB). Their goal? Digitize 150,000 pieces of content from communities across the nation over the next four years.

For those people working at a public media organization that’s participating in this massive undertaking, you’ll likely be packing up your old tapes, labeling them with metadata, and shipping them to a suburb of Philadelphia—specifically, to the studios of George Blood, LP.

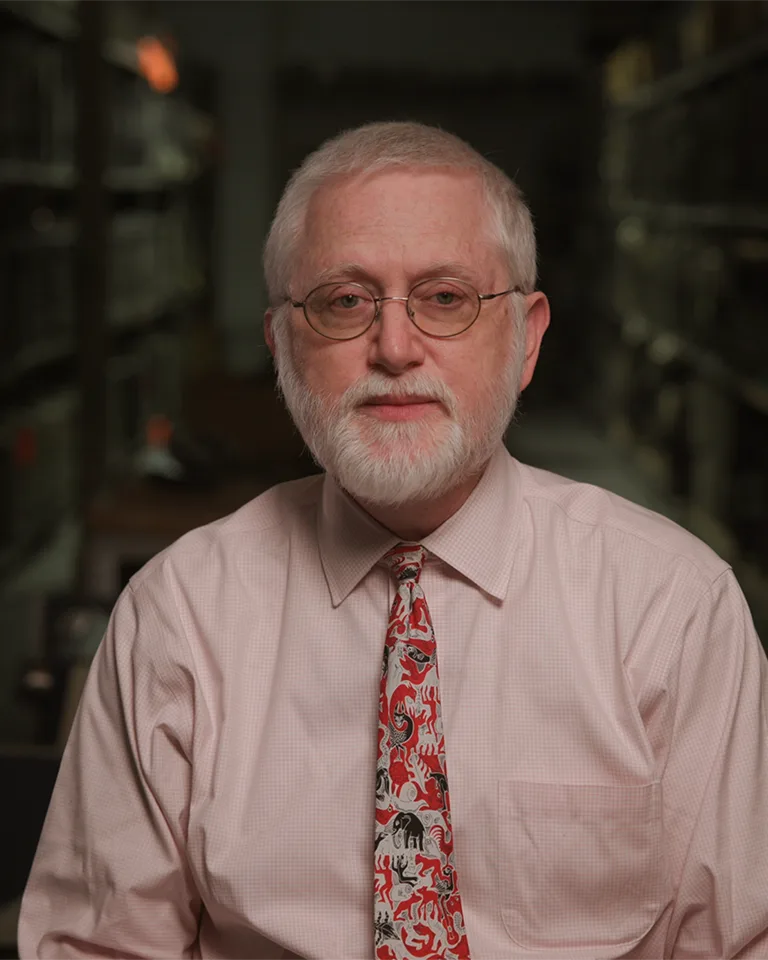

In this 40,000-square-foot production facility, owner and audiovisual expert George Blood oversees the transfer of thousands of antiquated tapes to digital files each month. Now-obsolete sound and moving formats are sent through equipment that facilitates the transfer, ensuring that the content is stored and plays back in alignment with today’s media landscape.

To borrow a phrase from the proverbial edit room, it’s where the magic happens.

Blood has been in the business for more than 40 years. His team digitizes some 400,000 tapes across more than 200 obsolete formats every year with the help of staff who are intimately familiar with the ins and outs of technologies past.

Owner

George Blood LP

“The issue of machine obsolescence is a non-trivial one. We’re fortunate in that at the scale we work at, we can throw the resources at some of these challenges.”

“When the materials come in—when Rose’s team is checking things in,” Blood says, referring to Rose Chiango, his colleague and point person on the AAPB project, they look to make sure everything is accounted for. “Are there more things in the box than are on the inventory? Which things are challenging in some way? Is the shell broken? There’s mold? Even at that stage, the person who’s handling the object is examining it.”

Their combined knowledge enables a relatively small group of people to save a large amount of content. Together, with very little fanfare, they are playing a pivotal role in the preservation of our history.

But there’s a catch. The equipment they depend on to transfer analogue formats to digital files may itself be heading toward extinction.

“The issue of machine obsolescence is a non-trivial one,” Blood says. “We’re fortunate in that at the scale we work at, we can throw the resources at some of these challenges.” In anticipation of the longer-term need for this type of equipment, Blood has amassed around 800 machines, purchasing many of them as soon as they went on the market for future use. He has more than 2,500 square feet dedicated to equipment maintenance.

“We are also very aggressive about acquiring spare parts, manuals. A facility will shut down and I’ll purchase the shop, sight unseen,” says Blood. “There’s a company that used to make tape-cleaning machines, and when the company went out of business, we bought all the spare parts.”

When his team finds manuals for old machines, whether at auctions, shuttered facilities, or online, they download PDF versions, ensuring they can hold on to the information in perpetuity. There are five staff people working on machine upkeep, the youngest of whom is in his 60s. Blood is keenly aware that for his work to continue, such knowledge must be handed down to younger, interested technicians.

“There are younger people here picking up bits of knowledge,” Chiango says, tech-savvy, motivated gearheads who are curious about how things work and who possess the invaluable ability to troubleshoot technical problems that may newly arise from bygone apparatuses.

Together with their mentors and teachers, today’s audiovisual technicians and archivists will see to it that the cultural heritage established through and by media will endure for new generations to learn from and enjoy.

The result of all this work is an American archive that will become a key resource at the Library of Congress National Audio-Visual Conservation Center, headquartered in Culpeper, Virginia. With its more than 90 miles of shelving for collections storage and 159 climate-controlled vaults, the 45-acre facility sits on the decommissioned site of a nuclear bomb–proof underground bunker originally built for the Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond.

The site now houses over six million audio and visual materials. With the ongoing additions of the AAPB materials, the National Audio-Visual Conservation Center will boast the largest and most comprehensive collection of moving images and sound recordings materials in the world.

Related