What Is More Dangerous Than Art?

It’s 2016. I’ve been incarcerated at Stillwater Prison for 13 years. Throughout that time, I’ve dealt with confinement as an artist. Among the many possible labels that could have befallen me—from both sides of the wall—I was respected among my peers as an Artist. We built a robust arts culture inside a complicated community that negotiated with violence and bartered in art. Which gave way to literature and poetry. When people paid attention—whether from the inside or out, we didn’t disappoint.

At that time, I was a “model inmate” at my pinnacle: running a full-time art department, managing a creative writing program, and facilitating restorative justice initiatives in my spare time. Then, the Department of Corrections decided I was a security threat—too much influence over staff and inmates. I was transferred immediately to a prison reserved for “shot callers” and “undesirables.”

I suppose, what is more dangerous than art?

Upon arriving at Rush City Prison, all my art supplies were confiscated. I was allowed 10 books, including sketchbooks, journals, and notebooks. Little did they know, I’m built to run on spite. Staring at a blank page, stripped down to pen and paper—an artist’s brush is just an interchangeable instrument, sacred yet replaceable. Prison does everything in its power to break your spirit—no less cruel than the hurricanes that smash the coast, no less vicious than the judgments of small towns. I needed to prove to myself that I was more than what the world said about me.

The Minnesota Prison Writing Workshop began in 2011 and was flourishing beyond the prison walls, which kept me connected to craft. Literature brought wonderment to my soul, and since I no longer ran the programs, I read more. I became addicted to chasing the spirit of the human condition in the depths of such American tragedy as mass incarceration.

Haymarket Freedom Fellow

“I needed to prove to myself that I was more than what the world said about me.”

By 2023, I’d published poems in my dream literary journals; done the cover art for the Washington Post Magazine; had Parameters of Our Cage, with Alec Soth, reviewed by the Guardian and the New Yorker; and edited the anthology American Precariat—projects unheard of from a prison cell. I was living the artist’s examined life from a cage when I found myself staring down another blank page. This time, it wasn’t for a publication, grant, or fellowship. I was writing my commutation speech to the State Board of Pardons requesting my release—a literal attempt to write myself free.

When I was named a finalist for the Haymarket Writing Freedom Fellowship, it felt like a win already. I was excited to leverage it against publication opportunities. I received the official news weeks before my hearing! Yet, I couldn’t tell anyone—this monumental validation created a calm in me. No matter what they did with my body, this was proof that they didn’t control my capabilities.

On December 19, 2023, my commutation was unanimous in my favor. After 21 years of incarceration, I stepped back into the world as an Artist.

It felt like the scene from the movie The Shawshank Redemption, when Tim Robbins emerges from sewage to take his first deep breath under the purifying rain. The Writing Freedom Fellowship gave me the grace to breathe after two decades of a trial by fire—where I used art to restore my humanity. For decades they silenced our achievements and dulled the desire to do more than sit in a cage because we might re-victimize family members—our voices went unheard.

Or so I thought. Thanks to the Fellowship, our cohort grows! Art is the most astute system of communication. Who thought they’d find such refinement in the trenches? We must show them. The Fellowship recognizes what it takes to remain an artist under the worst of circumstances.

I have taken that initial liberating breath—now I’m ready to get back to work—

Because, what’s more dangerous than art?

###

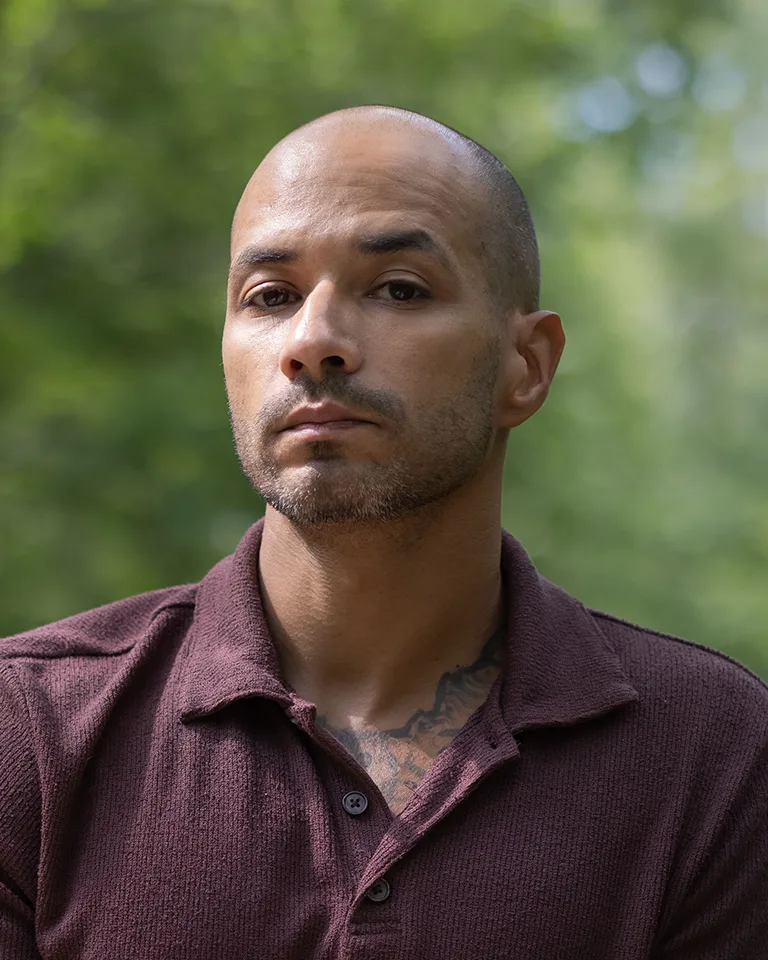

C. Fausto Cabrera is a multidisciplinary artist, writer, and social justice advocate whose work interrogates the human condition and transcends his 21 years of incarceration. As a Writing Freedom Fellow his groundbreaking work from a prison cell includes co-authoring Parameters of Our Cage with photographer Alec Soth, creating award-winning cover art and an essay for The Washington Post Magazine, notwithstanding serving as an editor on the anthology American Precariat.

In his first 10 canvases, the “Inherited Scars” series, Cabrera pioneers a unique artistic process that transforms trauma-related documents into handmade paper, creating powerful narratives of healing and redemption, shown at the Weisman Museum.

His work has been recognized with multiple PEN American awards, and his writing appears in prestigious publications including The Denver Quarterly, the Colorado Review, The Antioch Review, and Puerto del Sol.

As founder of C Fausto Consulting and Outlaw Excellence Productions, he bridges creative expression with social justice, working with educational institutions and mental health organizations to create lasting change.

The Writing Freedom Fellowship awards talented emerging and established poets, fiction writers, and creative nonfiction writers affected by carceral systems for their notable and necessary writing. Developed and administered by Haymarket Books in partnership with the Mellon Foundation and the Art for Justice Fund, Writing Freedom aims to recognize, support, and amplify the essential literary voices and contributions of those directly affected by the criminal legal system.

Related